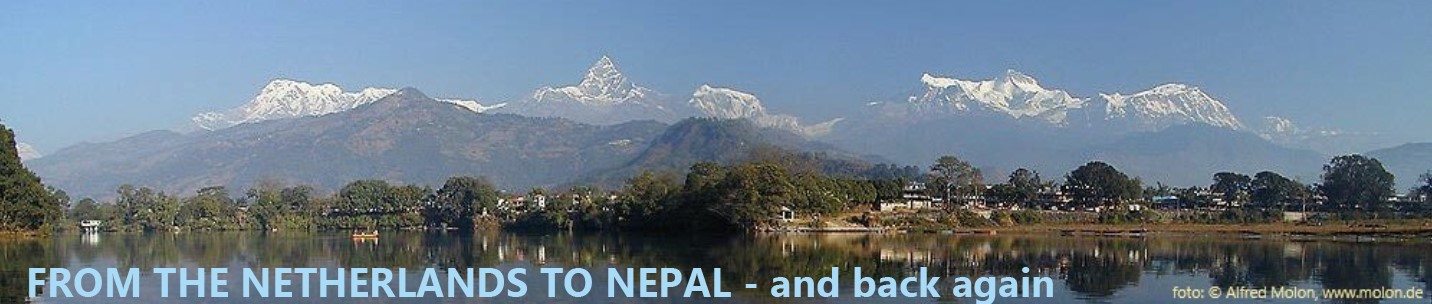

3. INDIA

India overwhelms you, overruns you, overpowers you. And if I hadn't traveled there by land, gradually getting used to sharper contrasts between rich and poor, poor hygiene and health care, extreme poverty, different ways and customs, dirt, dust and stench, India would have crushed me, for everything is intense there — not just the smells and colours but also the stench, the bustle, the poverty, the wealth, the indifference, the cordiality and the curiosity.

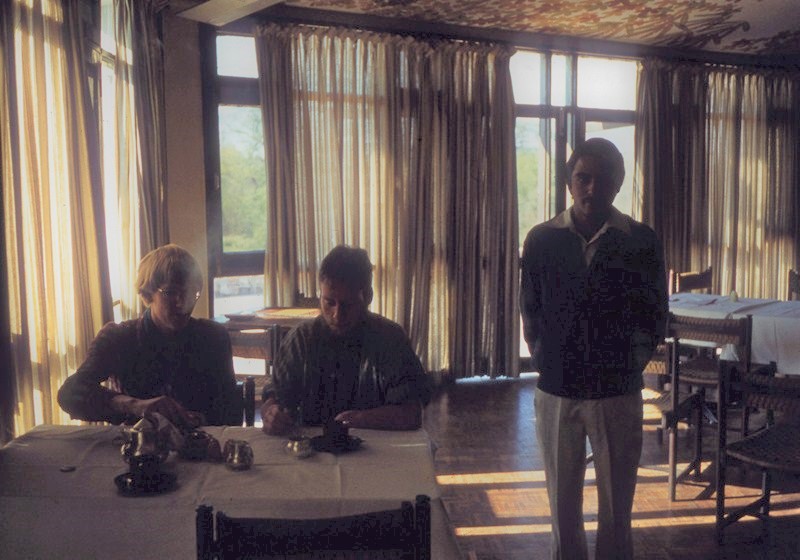

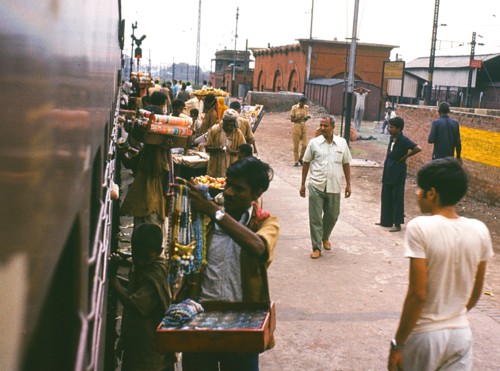

Any time we got off a train or a bus somewhere in India we'd be surrounded in no time by dozens of people, who all wanted something from you at the same time: Do you speak English, where are you from, are you married, what is your job, do you need a hotel, do you want peanuts/bananas/chai/head massage/shoe polishing/tangerines/taxi/rickshaw/etc? (Image: Keith Rajala)

Hotel Natraj housed at least as many Indian migrant workers as Western budget travelers. Walking from the hotel to Connaught Place the street corners in New Delhi stank of urine, the red expectorations of paan chewing men and women were visible everywhere, and the white stucco buildings and all the lanterns and bollards were smeared with the snot that people wiped off their hands. It was only when I traveled back from Nepal through India that I had gotten used to the poor hygiene level, but the stark contrast between rich and poor remained an intolerable reality.

On November 26, after three days in New Delhi, the banks reopened. While Cor made his way to the Bank of America to request replacement cheques, Frans and I went to the General Post Office (GPO; pictured here in a more recent photo). We were rather disappointed to find no mail waiting for us, but we had our own letters to post anyway. We had been told that in Indian post offices it was adviseable to have the stamps postmarked under your eyes so you knew they wouldn't be steamed off to be re-sold. At the GPO we waited for Cor and because of the heat we cooled down with a bottle of coke – Campa Cola that is, because earlier in 1977 Indira Gandhi's government had banned Coca Cola from India because "90 percent of India’s villages did not have safe drinking water, whereas Coke had reached every village”.

In the park on Connaught Circus we were constantly offered everything from freshly roasted peanuts to ear cleansing and head massages. That afternoon we bought tangerines twice and bananas twice, Cor had his ears cleaned, Frans had his beard trimmed, and I had a shave. On the way to the park we had seen posters for a concert that evening by sarod player Ali Akbar Khan, and one on Sunday evening by Japanese jazz musician Sadao Watanabe. (Click here for a great tune from that year.) Cor definitely wanted to go, so we decided to give it a shot and to our surprise and delight there were still tickets available. The concerts were great, but both started extremely late so we left before they finished. Watanabe's concert didn't start until midnight. with a break at half past two in the morning, after which we were too sleepy to stay for the second set. The contrast between the well-to-do crowd at the concert (Indians and Westerners) and the beggars, day laborers on their carts and cycle rickshaw drivers sleeping in the streets on the early morning walk back to our hotel is still vivid in my mind.

We had heard the stories about 'fortune tellers' who would try to wheedle you out of your money. They approached you out of nowhere at random places, but we wouldn't be so naive. Until a slightly shabbily dressed man with a gray beard and a turban caught our attention on November 28 with a few brief statements that seemed unexpectedly accurate. I suspect he had a trick to put us in a kind of trance very quickly, which enabled him to re-present our answers to his questions as if he were clairvoyant. When he was gone, Frans and I were each about Rs300 (about 60 guilders) lighter!

(Photo: Cor Kroon/Gerard Aartsen)

In the most unexpected places along the route from Istanbul, but especially in India and New Delhi, we came across second hand book traders with massive amounts of mainly English, but also French, German, Italian and even some Dutch books. In addition to discarded travel guides, these were titles that were popular among travelers, such as Jack Kerouac's On the Road and Dharma Bums, Robert Pirsig's Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Journey to the East or Siddharta by Herman Hesse, more spiritually oriented books by authors such as Vera Stanley Alder (Finding the Third Eye) and Paul Brunton (A Search in Secret India), who enjoyed renewed popularity among hippies since the 1960s, but especially bestsellers such as George Orwell's Animal Farm, Joseph Heller's Catch-22 or Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five, that were readily available everywhere.

These book traders offered a welcome pastime if you had to wait a day or more for a visa, or a reprieve for hungry travelers who were without money but still had some books to trade in. Often you could take out a book in exchange for two others. Because I saw it so often and the subject interested me, one day I decided to buy Erich von Däniken's Chariots of the Gods. The various archeological and paleontological anomalies that he described and his theories fascinated me and I subsequently found and devoured his other books too.

(Photo: Cor Kroon/Gerard Aartsen)

While waiting for Cor's new cheques, Frans and I advanced him his share in our costs and we traveled to some places around New Delhi. On November 29 we took the train to Mathura, which tradition says is the birthplace of Krishna, the eighth incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu. After Delhi, where a busy street ran behind our hotel, Hotel Nepal in Mathura was a peaceful oasis. But when we got to the town centre there was little of that left, with the streets again overflowing with cyclists, pedestrians, tongas, and motorcycles, and the occasional car trying to force its way through. In the temple at Vishram Ghat we were asked for money offerings at every corner, but our lack of religious aptitude made it all seem rather commercial. For another offering you could also wash your feet in the Yamuna river, where Krishna rested after killing Kamsa, the tyrannical ruler of Mathura. Because of a banner in the water showing a skull and bones, we decided the dust on our feet wasn't really bothering us that much.

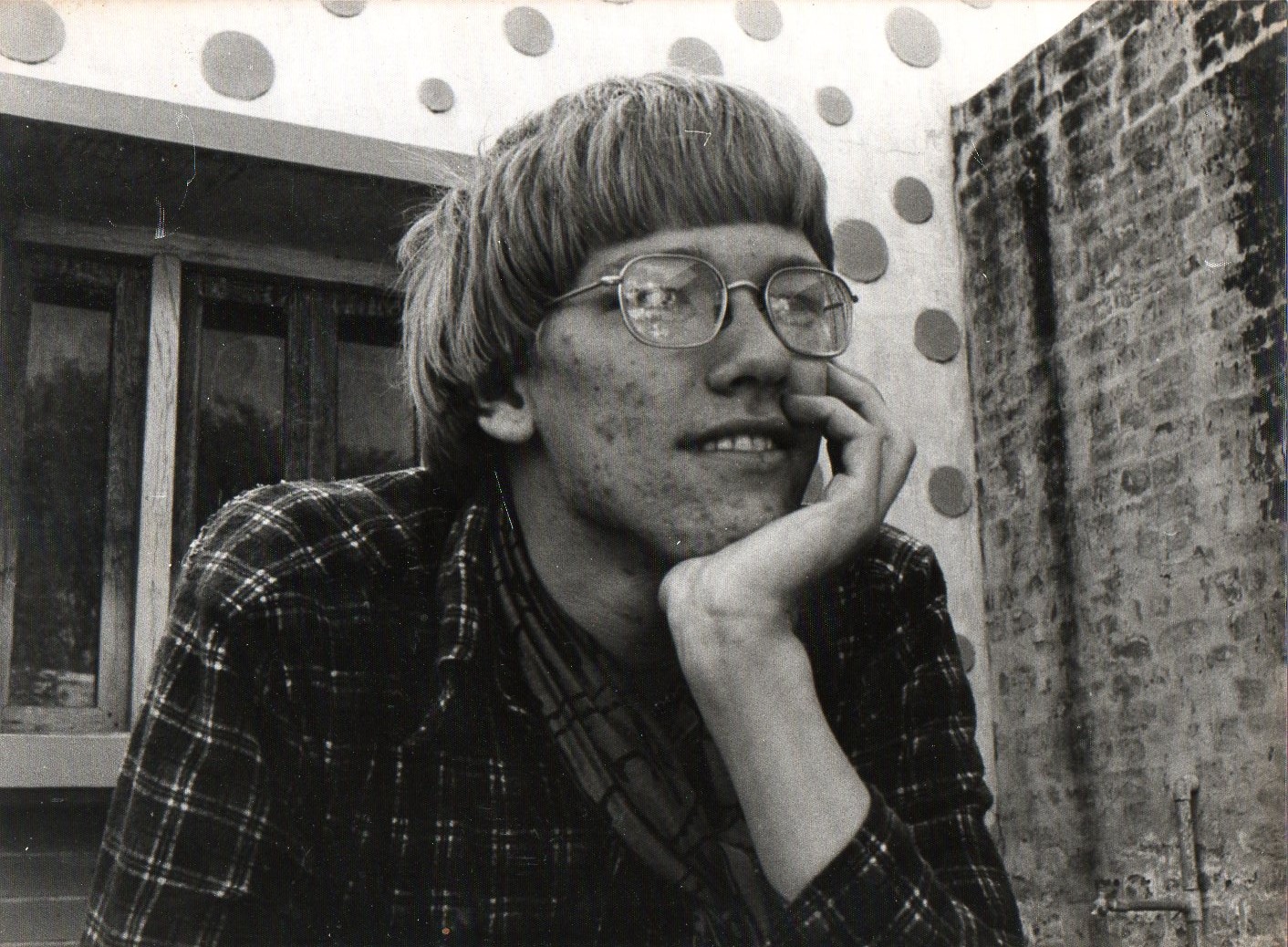

On the morning of December 2, Cor and Frans inquired if I was feeling okay again, since I hadn't said a word the previous day, not even good morning, of which I was totally unaware. That day I must have been entirely preoccupied with what I can only describe as a direct experience of the oneness of life — a sort of temporary expansion of consciousness. (It was probably on that day that Cor took this photo.) This experience, which I think must have happened in my sleep, was so overwhelming and comprehensive that it felt like a triumph to have my insights penned down in a long letter to friends, but when I got home I learned that precisely that letter had never arrived. Although I would experience regular bouts of inexplicable bliss in the weeks that followed, alternated with moments of chagrin when the heat or the crowds got to me, I only began to understand a bit more of my experience intellectually when I read a borrowed book on my return journey. (Also, I recently learned that experiences of this kind have been researched since 1973 by e.g. IONS and the Scientific and Medical Network.)*

In Hotel Nepal, like any other budget guesthouse, we quickly bonded with the house servant/room boy, who does all the chores for the owner and delivers any orders to the guest rooms. During our trip we had seen many times that if they were unlucky they were consistenly barked at and often treated as quasi slaves. As a guest you had the choice to (a) ignore it, (b) find another hotel, with a good chance that things were no better there, or (c) to treat the boy in question with respect and to give them a tip every now and then. My diary does not mention how the boy at Hotel Nepal was treated, but the night before we left I gave him one of the bottles of Golden Eagle beer I had bought. Moments later, he returned with two plates of snacks: "Ssht! No pay!" The next morning we decided to give him a good tip (Rs15) and a pack of Four Square cigarettes.

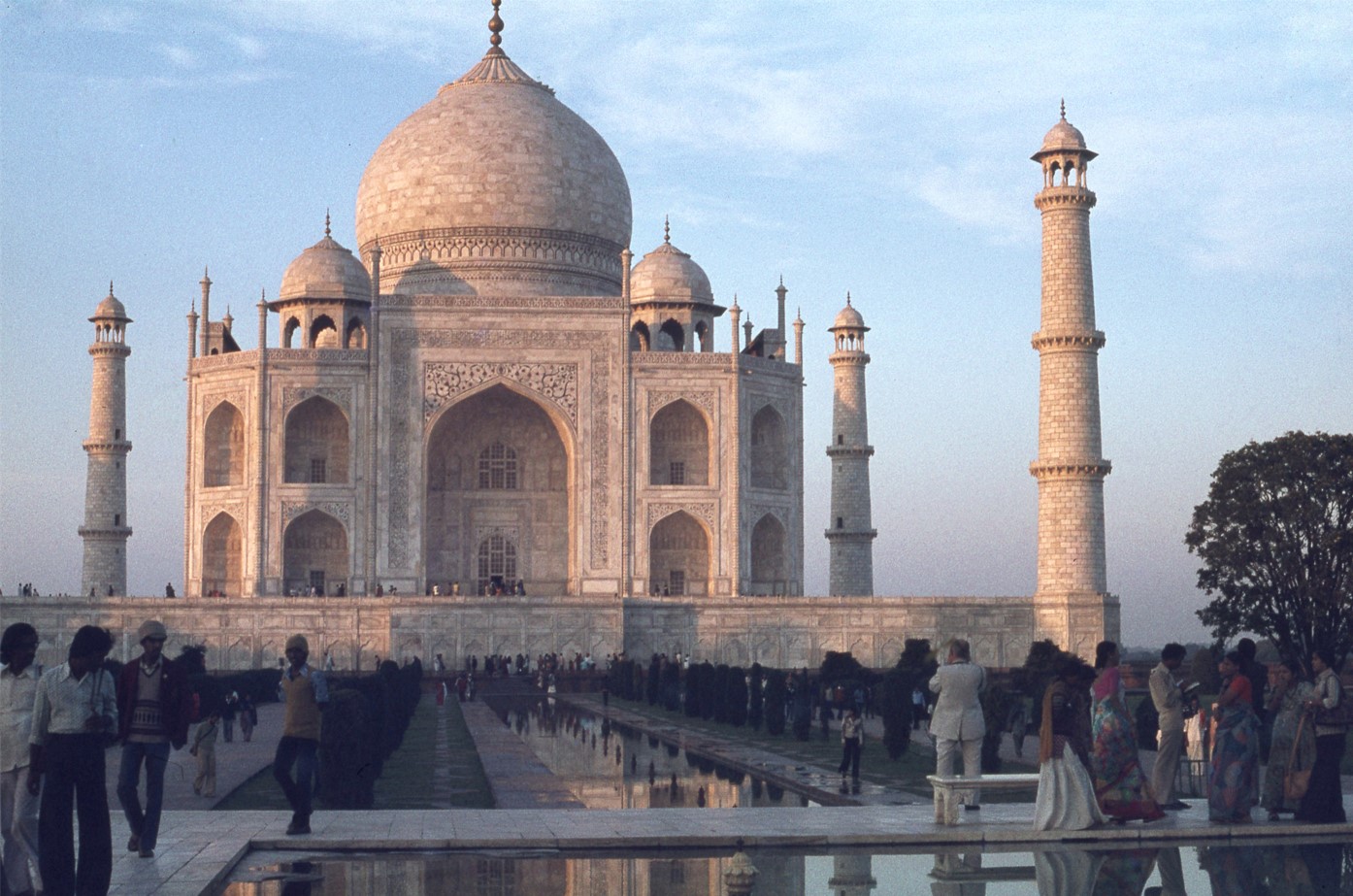

Saturday December 3 we took the train to Agra, where a taxi took us to the Empress Hotel. The co-driver offered to show us the Taj Mahal and the city for Rs5 each. The Taj Mahal was just as impressive as the descriptions suggest, but the tour of Agra turned out to be an attempt to earn a commission by taking us to various handicraft shops. Even though we were aware of the scheme we still arrived back at the hotel with a ring, a necklace, marble boxes, two chillums, a sandalwood Buddha and bookmarks.

Below: The Taj Mahal at sunset (Photos: Cor Kroon/Gerard Aartsen)

The day after our arrival at the Empress Hotel we were asked to leave, as a group of Americans would be arriving. We decided to take the bus to Jaipur in neighboring Rajasthan. Here we shared the room with an Australian we had met on the bus. The agreement was that the last person to leave the room would leave the key at the reception. Except our Australian roommate hadn't. The manager said there was no spare key, we just had to find our own way back into the room. No problem, said Cor, I'll break the lock from the door. (In budget hotels, all doors had a padlock.) That'll cost you, the manager said. No it won't, said Cor, because you're supposed to have a spare key. Suddenly a key appeared that opened the door to our room.

After the hustle and bustle of Jaipur we went to Bharatpur, where we wanted to spend some time away from city life at the budget hotel in the bird sanctuary, but on arrival it turned out to be fully booked. We were tired and hungry, but we were well out of town so we decided to walk to the only other hotel in the reserve – a swanky so many-star hotel on the edge of the reserve. When checking in, the receptionist's eyes lit up: "From Holland! Prince Bernhard was here last month! Boy, does he drink whiskey! Every morning, afternoon and evening!" The room cost Rs100 per night, a lot more than we were used to spending, but the ambiance was worth it. Dinner was also considerably more expensive than what we normally spent, but the Indian dishes tasted particularly good. They were brought to the table on serving trays on carts, so we almost felt like maharajas. For every dish the waiter asked if we wanted seconds, but not after our dessert, so I asked for a second helping myself which we were duly served. On December 9, I made the following clever note in my journal: "Walked along a trail in the bird sanctuary this morning, mostly a lake with dry patches."

(Foto: Cor Kroon/Gerard Aartsen)

Via Mathura, where we stayed another two nights at Hotel Nepal, we traveled back to New Delhi and we arrived there on December 12. To our disappointment, there was no mail from home waiting for us at the GPO. Waiting for news about Cors cheques, we spent the days in the park at Connaught Circus, where we had become familiar faces for many of the street vendors, and our hotel room. Like many travelers, we often spent the evenings playing cards. When after six days, almost a month after our arrival in New Delhi, Cor's cheques had still not been replaced, Cor suggested Frans and I travel ahead to Nepal, and he would follow as soon as possible. We had already arranged a visa for one month at the Nepalese embassy.

Frans and I boarded the train to Varanasi and Patna on December 19. By now we knew that it was possible to reserve compartment seats to at least be assured of a seat instead of ending up trying to secure a place in an ant tangle of travelers. I don't remember whether we avoided the tangle with our reservations, but we did have proper seats. If you asked for a reservation at the station, the ticket clerks were usually reluctant to oblige. The trick then was to demand to speak to the Station Master. This solved almost every problem you might encounter when purchasing a train ticket, even before a Station Master was in sight.

Our connection ran to Varanasi via Lucknow and Kanpur. In the very early morning of December 20, before sunrise, the train rode into a huge emplacement at Kanpur, where the train would wait for hours before continuing the journey to Varanasi. Luckily, the train master came to inform us about this layover, so we didn't have to worry. He even asked if we wanted breakfast before our journey continued. We said yes, and he made a note our order (toast, fried egg and jam, and coffee). Against all expectations, around 8 o'clock a waiter brought us a large tray with our breakfast. For us backpackers, this was an experience similar to the premier class service on the Thalys trains nowadays, and a somewhat miraculous one at that. From the train we saw rails and switches as far as the eye could see but no sign of human activity for miles around!

From Varanasi we continued by train to Patna, where we transferred to the trestle to the border with Nepal, via Muzaffarpur. This train actually stopped for every village boy who was taking his goat to the next hamlet, so when we arrived at the border we decided to spend the night in Raxaul, on the Indian side of the border. "Up early in the morning and on to Kathmandu."

* Only now, as I'm reconstructing my journey, do I see how this profound experience laid the foundation for the deep exploration of the oneness of life in my recent book, Pioneers of Oneness, which shows the correspondences between the latest insights from quantum and systems science, the Ageless Wisdom teachings, and the accounts about extraterrestrial visitors.

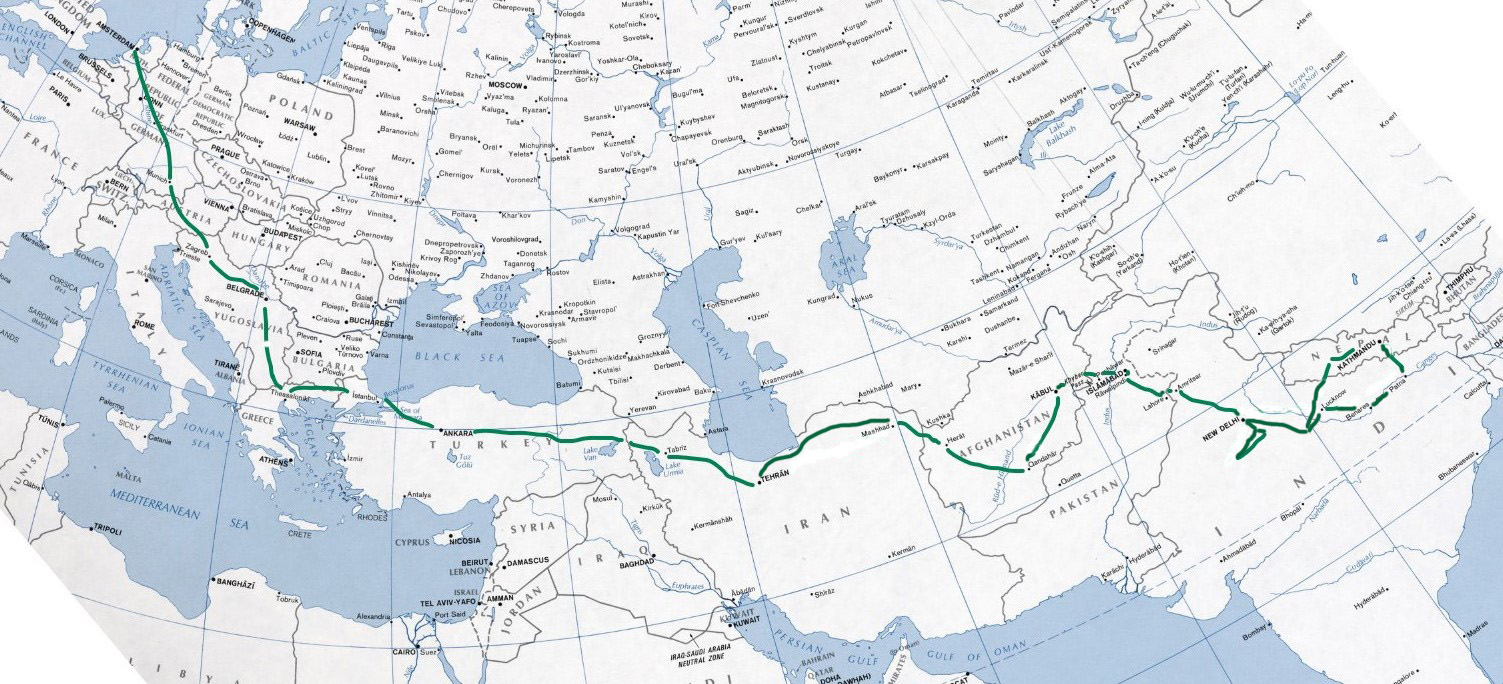

The journey

-

0. Prologue

-

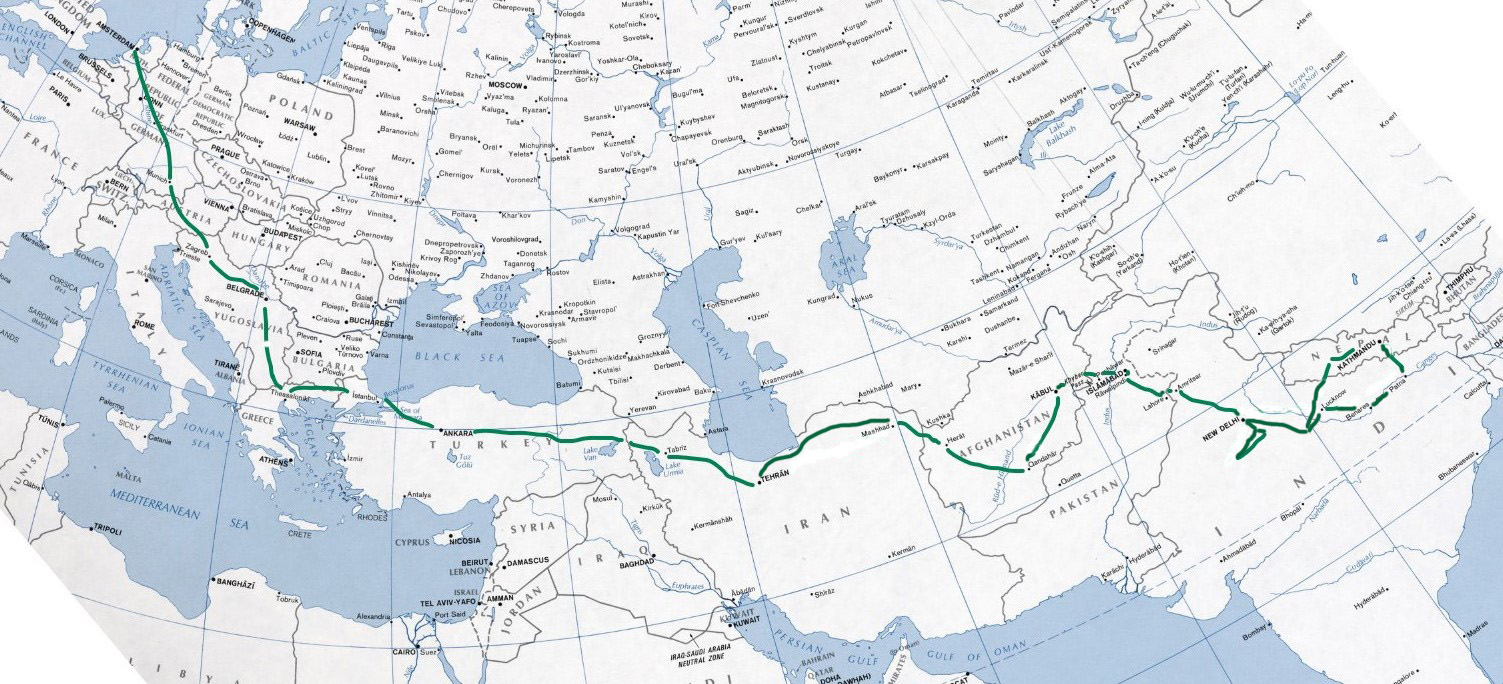

1. Amsterdam - Istanbul

-

2. Istanbul - New Delhi

-

3. India

-

4. Nepal

-

5. Return journey

-

Hippie trail resources